For Work-Life Balance, Look to the Labour Unions!

Work-life balance is a systemic issue that needs a systemic solution—not more tech, or coaching, but perhaps a return to good old labour union power. Sound crazy? Not as crazy as how busy we are.

It would be hard to count the number of times that a client has joined a session, late or having hopped directly over from another (online) meeting, and said, “Things are just crazy,” or, “I’ve been insanely busy.” Those words—“crazy” and “insane”—are used freely, and without due reflection. Are they really colloquialisms, or do they (unconsciously) mean what they say?

In other parts of the conversation, the theme of work-life balance will inevitably emerge. Even when the subject is leadership or communication skills, the questions turn to this topic. Some of my clients show me their diaries. They are not only back-to-back, but there are also numerous overlaps, sometimes three deep. Here's my verdict: it is insane. Things are literally crazy.

During performance related workshops, the question comes up about expectations; what to do about bosses and colleagues who send out emails late at night, expecting an immediate answer—or latest by the next morning? And what to do about the need to prove that you’re on top of things by meeting that expectation? I call it the “cult of busyness”, and point to “wearing busyness as a badge of honour”. What are we to do about that, comes the question.

Continue reading below, unless you’d like to…

…listen to the audio version:

…or watch the YouTube video:

What I notice is that everybody is looking for an individual answer, a personal solution, as though it’s their problem to resolve. I always ask myself; can nobody see the naked emperor? It’s all very well doing all you can to manage yourself, but what if the system doesn’t leave you alone? I try to steer people towards the idea that it’s a systemic problem and needs a systemic solution, but mostly I get met with blank stares. (I hope by writing it down here and showing some graphs, it will land with more impact.)

The short answer I would offer is that the epidemic of busyness and the dearth of work-life balance is driven systemically by what I call the “primacy of shareholder value”. In other words, placing profit over people. Despite all the talk of the “triple bottom line” (profit, people, planet), it seldom happens in practice. The systemic solution is to make people matter at least as much as profit. To achieve that, we need our leaders, those high priests of profit, to do more than just pay lip service to the “triple bottom line”. To get there, we ourselves need to stop worshipping at the altar of efficiency for the sake of shareholders. We need to start walking and working among the time poor (as much as I dislike that term, I shall use it here for its poetic ease).

The systemic solution is to make people matter at least as much as profit.

Here’s why I say this.

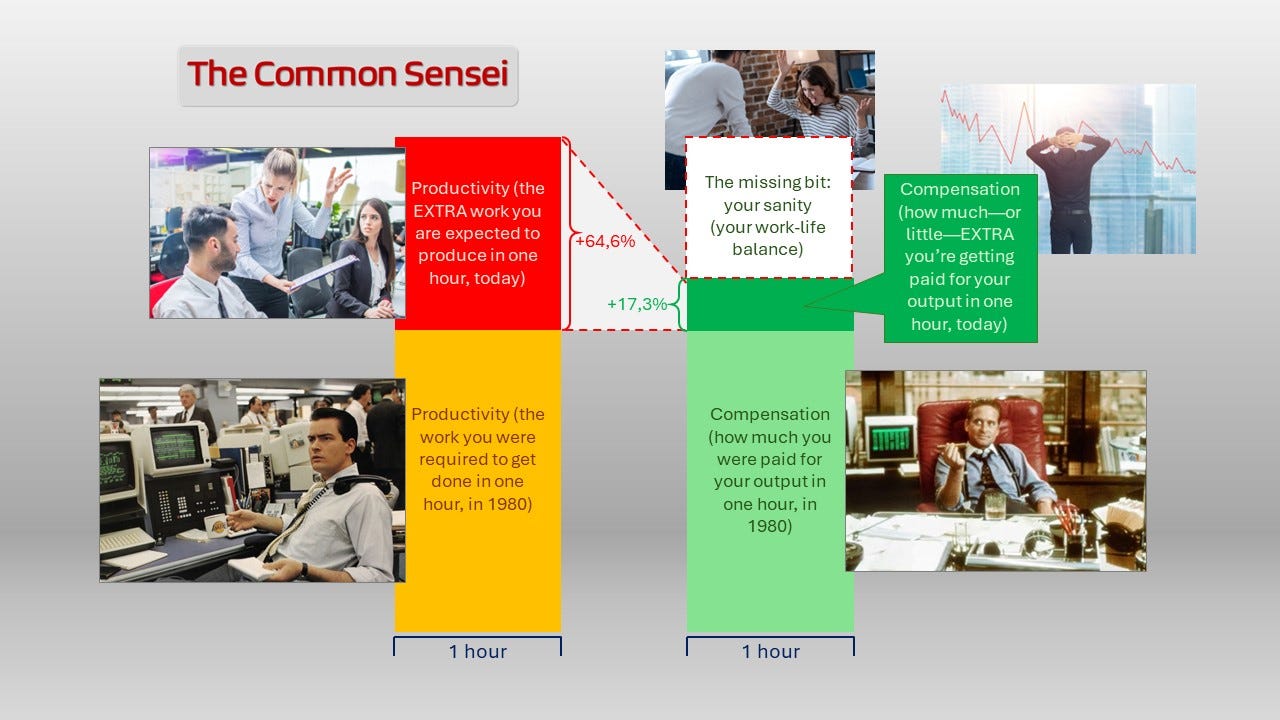

The image below is a screenshot taken from a free online course available on YouTube and via Substack called Wealth & Poverty that is offered by retired Professor Robert Reich, a prolific author, columnist and activist who was also the US Secretary of Labour during the Clinton Administration. He’s a fiery liberal, and I’m OK with that, but in case you’re not, don’t turn away. No matter your politics, it’s hard to deny the acuity and relevance of this graph with regards to our topic.

Productivity v compensation since 1980

The point is that, ever since 1980, productivity levels (the amount of work you’re required to get done in one hour) have risen way more than compensation levels (how much you’re getting paid for that hour). The numbers are 64.6% versus 17.3%. In other words, in any one hour, you’re expected to output an additional two-thirds beyond what you would have been required to produce in 1980, yet you’re getting paid only a tiny fraction more than what you got back then. And that gap is growing. Here’s another representation of that data:

Have you ever watched Mad Men? It shows how, back in the 60s, most middle-class people worked fairly regular hours, went mostly uninterrupted in the evenings and weekends, and could afford three or even five children with hardly a second thought. These days—and it’s not only due to invasive tech—we barely have a minute to ourselves, and most people struggle to afford one child.

In another lesson, Prof Reich points to what he believes caused this shift: the rise of “corporate raiders”, known today as “private equity managers”, a phenomenon that began in 1979, and which led to the shift away from “stakeholder capitalism” (where people mattered as much as profit) to “shareholder capitalism” (where people mattered only for the sake of profit). He explains it very well in this Substack post.

The glorious 80s, the waning of the unions

The glories of capitalism were given further impetus by the unprecedented material success enjoyed by the Western world throughout the 80s. We saw the rise of yuppiedom and the celebration of greed, both of which were superbly reflected in Brett Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho, and the movie Wall Street. Much of this was attributed to the “trickle-down” economic policies attributed to Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, but which were really the ideas of economist Milton Friedman. That era also saw the privatisation of public enterprises. Basically, organizations that existed to serve people became organizations that existed to serve shareholders.

In parallel to this was the systematic destruction and waning public perception of labour unions (also known in some countries as trade unions). Thatcher’s victory over the striking coal miners in Great Britain provides the most evident example of the systematic destruction of the unions. Trade unions were also increasingly associated with and accused of being, if not socialist, then certainly anti-capitalist. In South Africa, the unions were literally partnered with and led by members of the South African Communist Party, which fed extra fuel to their capitalist enemies’ fire. Unfettered capitalism received its ultimate debate-ending PR boost with the fall of the Soviet Union and the Berlin Wall.

From that moment on, we stopped questioning our servitude to the shareholders. Our conversion to the worship of efficiency—for the sake of profits—was complete.

From that moment on, we stopped questioning our servitude to the shareholders. Our conversion to the worship of efficiency—for the sake of profits—was complete. We came to see the profit motive as the panacea for all social ills. Problems with your country’s infrastructure? Just turn it over to the capitalists, and they’ll make it work. Social media? New technologies? Why, the capitalists know the answer. Don’t impose any restrictions, the profit motive will guide them to do what’s best. They are our prophets. Our prophets of profit.

Questioning the worship of efficiency

The Guardian technology writer, and academic, John Naughton seems to have noticed this too. In a recent post, he said, “When the history of our time comes to be written, one thing that will amaze historians is how an entire civilization managed to impale itself on its worship of optimisation and efficiency.” My phrase for this phenomenon is the “primacy of shareholder value”, and it’s such an unquestioned belief that when I throw it up in the air as being the cause of the work-life balance issue, I get blank stares in return. The emperor is not only naked, he’s invisible.

Of course, it’s true that there’s a lot to be said for the profit motive, but the question that’s not being asked is, at what cost? Well, at the cost of everyone—and everything—that’s not a shareholder. And that means you, the employee, the worker.

But hang on, there’s one thing we’re not seeing here.

We assume that those shareholders are someone else. Someone out there. “The rich.” That’s true only to a degree. Much of the shareholdings are held by pension funds, which is worker’s money. Which means we’re doing it to ourselves! Which means we could stop it if we wanted to. Which means that the problem, as Prof Reich points out, is not some evil rich people out there doing it to us. The problem is systemic. It’s the way we’ve allowed the system to be set up.

What can we do about it?

So, what can we do about it? Hire a performance coach (that’s me)! Ha ha. That’s what I should be saying. Instead, I’m pointing to something else. In the workshops, when faced with the question of what do we do about late night demands from our bosses, I suggest lobbying, by which I mean lobbying within the organisation for a shift in culture. Demanding that the leadership actually lives the values that are on the wall, values which often include something about the importance of people.

However, that only draws those blank stares. Nobody wants to risk it. I also know what it won’t be enough. I know that to shift this systemic bias towards creating shareholder value will require something bigger. Disruption. And I’m not talking about the trendy form of the word that points to digital disruptors. Nor the once-off climate and anti-war protests we’ve seen during the last two decades.

Why we should look to the labour unions

As Prof Reich says, those who hold the power that the system has afforded them—our shareholders—are not going to give it up voluntarily. The implication is that it will have to be wrested from them. That will require a disruption on the scale of the British Chartists, the suffragettes, the American civil rights movement, the antiapartheid movement. History has shown that a disruption on that scale requires serious organization and sustained effort over decades. It also requires withholding the most powerful negotiating tool that people have at their disposal: their labour. Yes, the very labour that is being given at an ever-lower price, at the expense of work-life balance. Hence the header of this article. Hence why this points back to the labour unions.

In a recent Guardian article, Astra Taylor and Leah Hunt-Hendrix, activists and authors of the recently-released and highly-rated book Solidarity: The Past, Present, and Future of a World-Changing Idea, explain: “[Labour unions are] critically important. They organise people to come together in the real world and to engage in a series of collective actions that ultimately can’t be ignored. At their best, unions facilitate collective discipline and long-haul dedication, enabling people to use a clear form of leverage: the withholding of labour.”

The reason why this is necessary, they say, is that, “The kind of solidarity required to secure a more … inclusive future will not appear spontaneously. It needs to be organised into being.” And, wham: “When we come together in an organised fashion—forging new self-conceptions, embracing radical visions and acting strategically—we can wield the power of numbers to disrupt business as usual, wrest concessions and pave the way for future victories.”

So, what would it take for you to get organised, to start lobbying, even protesting? And where would you start? Your boss? Your HR department? Your pension fund? It’s going to take time for this message to get through, so, for your children’s sake, best you start now!